Some time ago I taught a week long class in a fancy German hotel. It was the type of hotel where everything is perfect. So perfect, it made me a bit nervous. (What is this superspecial little knife for?!) Every morning, there was a breakfast buffet with every food you could think of. The chef stood in the back of the breakfast room. A young man with a stiffly ironed chefs’s suit and toque blanche on his head. He stood by the warm breakfast foods: scrambled eggs, bacon, fried tomatoes and boiled eggs.

Eggs with faces.

Those eggs were so out of place, that at first I didn’t understand. What is something so silly and joyous doing in our strict hotel? On the third day, I asked him. ‘You work so hard. This way you can start the day with a smile’. is what he told me. And it worked. In this sterile and stiff environment, I ate more boiled eggs than I ever have before.

Those eggs were so out of place, that at first I didn’t understand. What is something so silly and joyous doing in our strict hotel? On the third day, I asked him. ‘You work so hard. This way you can start the day with a smile’. is what he told me. And it worked. In this sterile and stiff environment, I ate more boiled eggs than I ever have before.

Homo ludens

I recently read Johan Huizinga’s masterpiece: Homo Ludens. A study of the Play-Element in Culture. It is about why we play: ‘In an imperfect world and in our confusing lives, playing achieves a temporary and limited perfection.’

Makers are the perfect Homo Ludens

My great love for the maker movement and all the makers, has to do with this. Dale Dougherty (godfather of the maker movement and founder of Make Magazine) has some nice words on this: ‘Makers are enthusiasts who play with technology to learn about it. A new technology is an invitation to play, and makers regard this type of play to be highly satisfying.’

Makers are the perfect example of the homo ludens. They make because they want to. Their drive to make comes from a place of freedom and curiosity.

Makers are the perfect example of the homo ludens. They make because they want to. Their drive to make comes from a place of freedom and curiosity.

Joyous yet dead serious

Huizinga also saw that a lot of play is very serious. Play creates order, is order. You see this in many makers too: despite the joyousness of making, it is also serious.

I find this to be one of the best recent examples: Arjan van der Meij made a chessboard that shows exponential growth: the first square contains 1 grain of rice, the second one contains 2, the third 4, and following that, 8, etc.

Why? ‘Math is a great passion of mine, so last summer, after I finished my Wilhelmusmachine, I started a different large math-maker project.’

A passion for the field, inspired by an interesting story; joyous and dead serious.

The Maker movement is en vogue

The importance laid on being able to do things yourself is a nice development in light of the former need to buy everything and to live according to the rules of the big corporates. It fits the zeitgeist: We are fed-up. We want to do things ourselves, we want power and strength, we want joy and we want it together. The drive to make is growing: today, more than 46% of Americans (135 million people) identify as being part of the maker community, both young and old.

And that is noticeable.

- The tech companies see makers as potential employees that are going to solve their predicted employee shortages. With full conviction, they support projects that stimulate interest and knowledge of technology. Big investments are being made in teaching kids to code, because we need programmers.

- The big corporations see making as a creative source. Designing by making and inventing is the perfect way to solve problems. If we can have children thinking about sustainability (for example) through a maker project, then you are killing two birds with one stone: you are supporting education and the younger generation and you are solving your own problems. (Check out Shell with their Generation Discover.)

- The edu-entrepreneurs see making as a beautiful way to package 21st century skills in a lesson plan or complete lesson package (including 3D printer). Schools buy an easy and fun solution to concretely teach those 21st century skills: using this lesson plan, you can do it!

Measurably useful work

The maker movement is growing up. We are able to measurably learn things with a teaching method, we solve concrete problems. We are able to formulate it into process, so that it becomes reproducible. And that can then be rolled out to those outside of the maker movement. Making becomes measurably useful work.

You could argue that the development described above is good. Within the Gartner Hype Cycle the maker movement has perhaps landed on the plateau of productivity. The utility is clear, the process is formulated into processes and systems. Making is mature and productive.

We are losing the best part….

And that makes me sad. And because of Huizinga (1938!) I understand why. To me the most beautiful thing about making is its playfulness, curiosity and openness. This playfulness leads to special things.

At the Bay Area Maker Faire they held a cupcake-race. Look at it. LOOK AT IT!

Huizinga describes play as the temporary erasure of the world. He would probably see the cupcake-race fitting into that context. It costs a lot of time, it’s crazy, strange and it makes me laugh so hard. It comes to mind often. It inspires me. I want it.

Productive!

The productive maker movement is a difficult one for me.

A characteristic of playing, according to Huizinga is that it’s free, that you do it because you want to and you can also stop when you want too. You do it your way with the conditions you make. It’s all in the hands of the player.

And this is the case for making as well: doing it and being lead by what you want and by what inspires you is what it’s all about. And that it leads to a product is nice, but the very personal process is at least just as important. A cupcake car is just as valuable as a solution to plastic soup. They both have personal meaning.

There is no contradiction

The contradiction between working and playing is false. In making there is both (serious) play as well as hard work. This is clear in a project like the Makerchallenge that is part of the Fablearn conf in Eindhoven this september, but also in the education of maker hero, Rolf Hut.

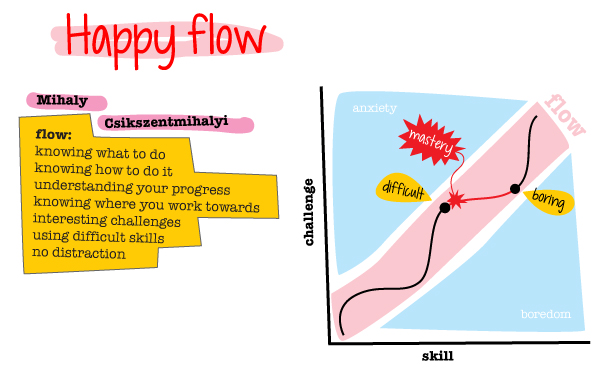

Rolf ‘MacGyver’ Hut teaches at the TU Delft and tries to stimulate the maker mentality among the first year physics students of the TU Delft in his class Design Engineering for Physicians. Rolf makes room in his lesson plan and assignments for the intrinsic motivation of the students; room for their own input and ideas. And if that works, you achieve flow.

Activities that initiate flow, are intrinsically motivating. You want to do them, because you are good at them. Or because you want to become better at something. Csikszentmihalyi states that when someone experiences flow, there is an optimal balance between what someone is capable of and what is expected of them.

Rolf Hut: Flow is different for everyone

But how to stimulate flow in your class?

Rolf: ‘Well, when educating it is of course difficult to give each student a unique assignment that fits their flow level due to differences in your group.’

My solution is to stimulate intrinsic motivation. You can achieve flow when the challenge is not part of the ‘class assignment’, but of your own assignment. In practice I apply this to my lessons by defining make-assignment very loosely. ‘Make something that illustrates a phenomena of physics.’ The benefit of this is that students will make something that they have always wanted to make ‘Oh, then I’m going to make a Tesla-coil!’ As a teacher it is the art to channel that enthusiasm toward something that is achievable for that specific (group of) student(s): ‘A Tesla coil is quite deadly and often doesn’t work, but have a look at slayer exciter‘.

This results in a ratio between planned learning goals versus collateral learning, that is leaning more towards collateral: you can’t a priori determine what students will learn even if you know that they will learn something. It will differ greatly per group.

Furthermore, there is a low bar for what is necessary to pass the assignment. Students with little intrinsic motivation will do the bare minimum to pass. Normally these are the students you lose, because they don’t pass a class exam, but with maker education they will make something minimal that meets the requirements, but clearly isn’t inspiring. They have achieved the minimal learning goals, but not the collateral learning. At institutes where your fellow teachers are watching your methods (and rightly so!) it can create an image of education that is too easy.

It may indeed be bad for a small minority of students. However, the larger majority challenges themselves and with a nudge from the teacher they get into flow.

To summarise: achieving flow with a group of diverse students is done by giving an open assignment and pushing individual students towards make-projects that are achievable for them. This means that it is difficult to determine what learning goals a student will reach, but what is certain is that they will learn something new.

Thanks Rolf!

To me the playfulness finds itself in the individuality. The space that the students take and fill. The authors of the makered standard work Invent to Learn describe this as well. Watch out for TMI:

- Too much instruction

- Too much interruption

- Too much intervention

But leave room for the (playing) maker.

Find the balance

We have to trust that something is being learnt. So please everyone, be careful:

Companies that are ordering future employees: let it go. You can inspire children, but you can’t force them. Be careful with your lobby and collaborations with schools. Know your place. Pedro de Bruyckere (Belgian expert on education) said it well in an interview on digital skills. Paraphrased: ‘Programming is merely one of the inspiring things that you want to show children. Just like philosophy or gym. And if you do that on the conditions of the children, they may become inspired.’ Try that, but don’t force it.

Corporations, make sure you keep you integrity. Do not make children responsible for your bad policies of the past. And if you want children to cooperate then ask what they want and truly do what they ask. Leave it up to them. And marketers: be careful with your logo and PR team in the class; are you working your magic for the company’s reputation or for the benefit of the children?

Edu-entrepreneurs, if you want kids to make, then respect the beauty of it. Do not stifle it with processes and methods and measurability. Trust the makers, no matter how young they are. Do not focus purely on short term utility, but focus on growth of the students (long term). Give teachers the inspiration to do the work in their own ways. Then it will become useful on its own. (And many of the 21st century skills have already been a big part of education anyway. Embrace that.)

Be careful not to judge the maker movement by outcomes

The grand Dale Dougherty told me:

Sharing is love

Huizinga also celebrated the lack of economic purpose in play: Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it. Again, makers are like this too. What they learn, they share and what they want to know they ask. They search together, find together and share it all for free.

If you step into making, consider becoming a part of that. Don’t just take, but also give.

And play!

Like my dear maker friend Arjen van der Meij said on twitter: I don’t have time anymore to make non-joyeus projects. Well Arjan, neither do I.

Love <3

(This story by Astrid Poot was originally published in Dutch. Translation was done by the great Lydia Kooistra.)